It was just one night, and one night, measured against the course of a lifetime, doesn’t seem all that significant. But it was a dark night, and I have never been able to shed the weight of the memory of it. I have never been able to put it, as they say, in perspective. I never will.

It was just one night, and one night, measured against the course of a lifetime, doesn’t seem all that significant. But it was a dark night, and I have never been able to shed the weight of the memory of it. I have never been able to put it, as they say, in perspective. I never will.

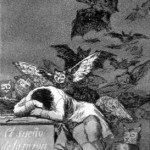

Jasper was not quite six months old. I had not slept in weeks. I lay awake as he stirred and fussed, bracing myself for the moment when I would have to rouse myself fully to nurse him or change him or soothe him. The darkness that night seemed particularly black, the kind of black that has a density, a weight. To say that it felt like it was closing in would be to use a trope that gets overused when writers are trying to describe dark nights and oppressive fear, but in this case it was true. The darkness was closing in on me like a heavy fog, like an army of ghosts, like a slick of oil, like night made solid and sinister. I couldn’t breathe. Jasper continued to fuss. I fought the dark.

I fought the dark. I think that I won. Even at the time, I wasn’t sure. I’m still not sure.

Later, when I wrote about what happened, I couched it in the most delicate of terms. “I was groggy,” I said. “… (I was) confused, disoriented, as I held my squirming baby in my arms:”

He fussed, breathing heavily through a stuffy nose, truffling for the breast and then pushing it away. He squirmed and kicked and protested and snuffled and grabbed and pushed and with every kick, every push of his fierce little legs and arms I struggled toward wakefulness, needing to be awake, needing my strength and my composure but wanting oh so badly to just let the darkness overtake me and to slide back into oblivion. But he wouldn’t let me, he was too uncomfortable, poor thing, hungry and snuffly and demanding, he would not let me let me go and he would not let this be easy and in a flash, in one moment, I felt the frustration course through me like a current and there it was, for a split-second – a split-second and an eternity all at once – ANGER – sharp and hot and as I felt the tears prick my eyes and a sob burble in my throat I was overwhelmed by the brief flash of an urge to just drop the baby, just drop him to the mattress and throw myself off the bed and stomp away into the night.

I didn’t have an urge to drop the baby. I had an urge to throw him. And then to throw myself, right out the window. It was an fleeting urge, one that passed, as I said, in a split-second, but it also felt like an eternity, an eternity during which I was not in my right mind, and completely aware of not being in my right mind, and completely helpless to do anything about it. It was the most terrifying moment of my life. It was the moment about which I feel the most – the most everlasting – shame. In that moment, I was – or almost was – one of those mothers, those mothers that you read about, the Andrea Yateses, the horrible, terrible mothers who put their children in the car and drive it straight into the lake. I was a bad mother. I was a bad mother, the worst mother, the most horrifyingly terrible mother possible.

I sought help from a psychiatrist, but I downplayed the grimmer details. I am not a bad mother, I told myself. She will think that I’m a bad mother. I’m not a bad mother. Am I a bad mother? I denied parts of my own story. I denied having wanted to harm myself. She read me the referral report – reports intrusive thoughts… wanted to harm baby… – and I recoiled. It hadn’t been exactly like that. It was more abstract than that. I hadn’t been in my right mind. I hadn’t been in my right mind. But of course, that was why I was there, wasn’t it? In a psychiatrist’s office? I hadn’t been – I wasn’t – in my right mind.

Of course I wasn’t. I was depressed. I was suffering from postpartum depression, acute postpartum depression, acute postpartum depression bordering on postpartum psychosis. But even knowing that – even having a very firm grasp of that, having struggled with it for nearly three years; even having written at length about that – I was still ashamed. So ashamed, that I only went back the psychiatrist once after that. I took the prescriptions – leaving them unfilled, because I was still nursing, and shouldn’t a good mother continue to nurse her baby, regardless of her mental state? – and left after the second visit and never went back.

I didn’t have any more psychotic episodes. I continued to write about my struggle, which allowed me to gain – again, for lack of a better word – perspective on it, and which ensured that, in addition to my anxious husband, there was an army of sympathetic supporters – you, all of you – keeping an eye on me. But I still struggled with the shame and I tempered my stories, omitting the more depressing or frightening details of my experience; I hid my shame, I denied my shame. And I never went back to the psychiatrist. I was too ashamed. I was too afraid of talking, out loud, about whether or not I was a bad mother.

Even though I knew – even though I know – in my right mind – that I am not a bad mother, still… I came too close to being one of those mothers. I came too close.

And therein lays the problem. We still slip too easily into thinking of those mothers as those mothers, as bad mothers, as the worst kinds of mothers, as other. These are mothers who have fought depression and lost. These are mothers who didn’t have support. These are mothers who might have had support, but were too ashamed to ask for it. These are mothers who get described, in articles like this one posted today at AOL, as ‘psychopaths’ and ‘cold-blooded criminals.’ Bad mothers. The worst mothers. Mothers whose path, but for the grace of God and Ativan and the Internet, any one of us might have taken. I might have taken.

We have an emotional investment in characterizing these mothers as bad, as other. We want to keep our distance. We want there to be a clearly recognizable line between the mom who struggles and the mom who harms. We do not want to say, there but for the grace of God go we. We want to say, we could not possibly go there. That is a place to which we will not, can not, could not go. But in saying so, we put ourselves, and our children, at risk. In saying so, we create monsters, and in creating monsters – creatures that lurk in a netherworld that is foreign to us, closed to us – we shame, and in shaming, we close off the possibility of understanding, and of battling, the darkness that produces these so-called monsters, these so-called monsters (these monsters who are not monsters, who are not monsters; repeat, repeat, repeat) who might – but for the grace of God, but for the grace of good psychiatric care, but for the grace of community support – be us.

This is not to say that every mother who harms her child is struggling with postpartum depression, or any kind of perinatal mood disorder or non-perinatal mood disorder or depression or mental illness. This is not to say that there is no such thing as abusive mothers. This is not to say that there is no such thing – no such person – as a really bad mother. It is to say that blanket characterizations of mothers who harm their children as cold-blooded and shameful and bad – as does the horrifying, appalling article posted at AOL – can have a terribly – possibly deadly – effect on women struggling with the darkness, inasmuch at these deepen and perpetuate the shame associated with that darkness. A mom that is ashamed of what she is going through – a mom who fears being labeled ‘bad’ because she is battling darkness at a time when she is supposed to be – supposed to be! – dancing in the light – is a mom who might not admit to what she is going through, a mom who might not seek help, a mom who might not get help.

A mom who might find herself, in the dark of night, battling a demon that she cannot fight on her own, and lose.

*Apparently, AOL has edited some of the original comments out of the article. That there was such an article in the first place, one that focused entirely on one ‘expert’s’ claim that mothers who harm their children are all cold-blooded criminals, is still evidence of the deeper problem that I’m speaking about here. (See also Katherine Stone’s excellent post on the subject, in which she cites some of the original remarks.)