Sometime, about two years ago, I started closing comments on posts. Not all of the posts, all of the time, but some of them, some of the time. I started doing this, not because I’d stopped loving comments – who, who has ever blogged, has not loved comments? – but because I loved them too much. They had become too important. I had become aware that I was, at times, writing for the commentary, for the response, for the conversation. Which was fine, of course – the discursive character of this space is what makes this medium powerfully different from others – except when it wasn’t. There were times when the pull to conversation was, I felt, distorting my story. Distorting my motivation.

Sometime, about two years ago, I started closing comments on posts. Not all of the posts, all of the time, but some of them, some of the time. I started doing this, not because I’d stopped loving comments – who, who has ever blogged, has not loved comments? – but because I loved them too much. They had become too important. I had become aware that I was, at times, writing for the commentary, for the response, for the conversation. Which was fine, of course – the discursive character of this space is what makes this medium powerfully different from others – except when it wasn’t. There were times when the pull to conversation was, I felt, distorting my story. Distorting my motivation.

I worry about how my own narrative impulses impose a certain form and structure and feel to my life and the lives of those around me, not least when I consider writing about the most difficult things, like depression and anxiety and grief – have I written myself and my loved ones into a story that is all about struggle? Am I turning my struggles (to say nothing of my victories) into spectacle, and to what effect? I turn off comments on some posts – some posts about my father, for example, some others about my children, many about Tanner – when I want to remain clear with myself that I am writing for myself, and not for reactions, when I want there to be no mistake that I am not writing a given story for attention or positive reinforcement.

There is an argument to be made, of course, that we all write for attention and positive reinforcement. That there is no pure writerly motive for writing, such that one might spill one’s words across a page and then submit them to flame, or the delete key. If I wrote only to gratify my own desire – my own need – for writing, I could write in a personal journal, or on a password-protected blog. But I don’t, because I do, like all writers, want my words to be read. I want them to be absorbed and digested and reflected upon. I want them live outside my own head, to be set free in the world, to have a life of their own. Turning off comments is not a denial of that life. It’s a decision to not participate in that life, to not be personally, emotionally invested in that life. It’s a decision to put the words out there, and let them be. To have my personal, writerly relationship with those words, and to let others have their own readerly relationship with those words, and to not seek out a harmony between the two.

Why, then, not close comments on all posts? Because, as I said the other day – on, as it happens, a post on which I closed comments – the dialogue that emerges from commentary is important to me, as is – obviously – the community. Turning off comments sometimes is just a reminder to myself that I do not write – primarily – to generate vocal response; it keeps me honest about why I’m writing about certain things, i.e. because the story demands to be told, and not because the story will yield a certain response.

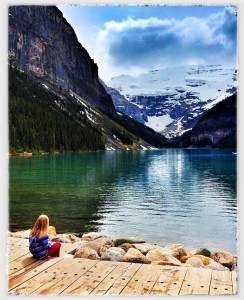

And here is where my figurative feet get tangled: the dialogue from – with – the community creates its own story, a story that is always worth telling. Regardless of whether that commentary is positive or negative, supportive or damning: there is always a larger story to be told in the conversation that is woven out of the narrative thread that the original author puts forward. This is the glorious, messy postmodern character of this medium, this space: it moves and thrives according to its own chaotic lights, that drives without a map, that puts the author (the capital-A ‘Author’) in the backseat and refuses to take her advice on what route to take or whether to slow down on yellow. And sometimes that story is better, greater, than the small story that the Author clutches to her chest. Perhaps that story is always better, greater. It has certainly been better, greater, for me, at times: the community story around Tanner, for example. The community story around my lost brother. The community story around the boys and girls of Lesotho and Uganda. The community story that we are telling here, this month, with Shot@Life – the community story that is saving lives, and inspiring a community to tell stories – to share stories, to create, together, stories – to change the world.

This community story is one that can’t be owned or authored by any one person; its beauty, power and magic is that it is diffuse, diverse, shared, collaborative, collective. That it is vast, and contains multitudes. It contains poets and philosophers and activists and entrepreneurs and artists and ordinary people that are all of those things, and more. It contains friends, and critics. It contains wit and intelligence and absurdity and error. It is formidable, and ridiculous. It is the source of more inspiration than I ever thought possible.

So. I am being selfish when I hold the community at bay and keep my story to myself, when I insist upon being modern (contra postmodern) in my ownership of my story, in my authorship of my story. And I will continue to be selfish, sometimes, because it is my prerogative to be selfish, and because being an author is, by definition, to be selfish. But I will also celebrate my moments of generosity – no, not my generosity: your generosity, our generosity, and the moments in which I open myself up to that generosity – and the epic, culture-changing project that we are driving forward. This culture-changing story that we are driving forward, this culture-changing, world-changing, life-changing story of which we are all authors.

This story in which we – you, us, this community, this inspiration – change the world.

I mean that. This post is part of Blogust, Shot@Life’s Blog Relay for Good in which 31 bloggers, one on each day in the month of August, are writing about people from our communities who have inspired us. Each comment made on this post – all month long – will unlock a $20 donation to Shot@Life up to $200,000 to vaccinate 10,000 children in the world’s most vulnerable places. $20 is what it costs for one child to receive 4 life-saving vaccines: measles, pneumonia, diarrhea and polio; preventable diseases

Keep at it.

(Tomorrow, Tracey Clark picks up the narrative baton and runs forward. Follow her.)