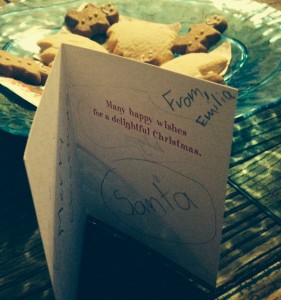

Tomorrow is Christmas Eve. Tomorrow night, Emilia will put out cookies and milk and a handwritten note for the red-suited gentleman who will visit our house – ingress through the chimney – and leave presents under our Christmas tree. She will also leave carrots, for the reindeer who pull his sleigh, because, as she says, there are no reindeer gas stations at which to refuel one’s reindeer on epic all-night round-the-world road trips.

Tomorrow is Christmas Eve. Tomorrow night, Emilia will put out cookies and milk and a handwritten note for the red-suited gentleman who will visit our house – ingress through the chimney – and leave presents under our Christmas tree. She will also leave carrots, for the reindeer who pull his sleigh, because, as she says, there are no reindeer gas stations at which to refuel one’s reindeer on epic all-night round-the-world road trips.

Emilia is nine. She just turned nine, but she is nine nonetheless, and in some ways she’s really nine going on nineteen. I wondered, as we approached the holidays, whether this would be the year that she called our bluff on Santa. She did not. In some respects, she doubled down on Santa, writing him multiple letters (one original letter, and about a half dozen addenda: “I KNOW I ASKED FOR (American Girl) JULIE’S CAR BUT IF YOU DON’T HAVE ONE THAT’S OKAY YOU CAN BRING ME HER BED INSTEAD. ALSO PLEASE SEND MINECRAFT LEGOS TO JASPER HE FORGOT TO ASK FOR THEM.”) She loves Santa. She loves the Santa that lives at the North Pole and she loves all the ‘helper’ Santas who are dispatched to act as Santa Ambassadors at shopping malls and Christmas parties and she loves putting on her own Santa hat and pretending to be Santa. Santa, for Emilia, is the very embodiment of generosity and happiness and she can’t get enough of him. And all of this is fine by me. I am happy for it to continue as long as it continues in what ever form it continues and I will do everything I can to safeguard the possibility of it continuing as long as I can.

I know that not every parent feels this way. This is the time of year when op-eds about telling the ‘truth’ about Santa abound. This is the time of year when adults publicly parse their discomfort with the Santa story and take their stands against children being misled by that story. I just can’t do it, they say. I just can’t shake the feeling that my children need to be able to trust that all their parents ever told them was the truth. This, because the story of Santa is, of course, not true.

Of course.

If you were to ask me, casually, if I thought that the most familiar Santa stories – ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas, Rudolph, et al. – were based on fact, I would, of course, say no. I don’t believe that a large man in a red suit runs a sweatshop, exploiting cheap elf labor, at the North Pole. I don’t believe that he keeps a list of who’s naughty and nice, nor that he flies around the world Christmas Eve, dispensing gifts and small bits of coal according to the dictates of that list.

I don’t believe that reindeer really do know how to fly.

But neither do I believe that Santa stories are lies.

A very long time ago, long before there was a Christmas or a Santa or anything of the sort, Plato argued that there is a very important difference between what he called lies of the soul and verbal lies, or lies in speech. A lie of the soul, he said, is a lie that misguides the soul, that misdirects the soul away from truth. It’s a lie that causes the soul to become confused, and so, ultimately, unhappy. A verbal lie, on the other hand, might be as simple as a little white lie, told to avoid hurt, or it might be something more noble. A noble lie is a lie in the sense that it veils the truth, but it veils the truth in such a way as to make it comprehensible to those who are unable to perceive the truth in its fullness. It orients the soul to truth, without revealing truth openly (the truth being like the sun – its brightness is so intense as to be blinding, and so we must, most of us, protect our eyes.)

When I used to teach the story of the noble lie (which appears in Plato’s Republic) to my undergraduate students, they usually responded, initially, with indignation. A lie is a lie, they would say. It is meant to deceive, and deception is bad. Yes, I would answer, deception is bad. But not all fiction is deceptive. I would remind them of origin stories; I would remind them of folklore and myth; I would remind them of fables; I would remind them of the stories that we tell children, of the stories that we use for the purposes of teaching.

Stories like the story of Santa, which, I think, teaches something about generosity and goodness and the idea that all children deserve love. That the best way to celebrate Christmas is to give gifts without the expectation of reciprocation, to give because giving is its own reward. That the most meaningful kind of giving is the kind that quietly drops a little happiness into the figurative stockings of others and then slips away, red-cheeked and joyful for having shared such happiness. (We could, of course, go darker with this story, and expand upon the ‘naughty and nice’ proviso, and say something about cold and coal-dark hearts being undeserving of gifts, but I am skeptical of the quote-unquote truth of this part of the story and so I will likely – because it does not accord with the quote-unquote truth that I wish to communicate to my children – delete it from the version of the story that I tell them. Such is the power of the parent, who as primary storyteller is both poet and philosopher-ruler.)

(I could, of course, say something here about religion and the original story of Christmas and the purposes that these stories serve and what it might mean to refer these stories as noble lies. But that is a much longer and more complicated post and so you must just accept these concerns as subtext.)

There is, of course, more to this than the question of whether such stories are deceptive. Some parents teach their children that Santa is a character of fiction, no more real than Muppets and superheroes and fairy tale princesses. Which is fine, I think – except that when I think of my own childhood relationships to characters of fiction, what I remember most fondly is the wonderful uncertainty of those fictions. Grover might have been real (I still experience shudders of disappointment when I see pictures of Muppets lifeless in the hands of their puppet-handlers). So too Peter Pan, and Alice and the Cheshire Cat, and the Tooth Fairy. And Santa. Those characters, and so many others, were fascinating to me because they made demands upon my imagination – they lived only through my imagination, it was my imagination that sustained them, that made them walk and talk and breath. Had they solely been one-dimensional figures, words and pictures on a page, had I been certain that they were not real, they would have remained flat. Lifeless.

Their stories had force, for me, precisely because those stories occupied and energized that wonderful space between my heart and my mind where truth and story and fact and fiction are blurred, where the impossible and the not-quite-possible and the possible become deliciously tangled, where disbelief is always suspended. They lived – they live – and became real in the space of my imagination.

I have never tried to convince my daughter that the Santa in the mall is the real Santa (on the contrary, as I said above: these are ambassador Santas. Helpers. The real Santa is far too busy to sit in a mall all day.) I will never insist to her that there is, in fact, a real man in a red suit living at North Pole with a harem of elves. I will never try to make her believe. I will, however, tell her stories about Santa (of all varieties), and I will tell these in my most assured voice, with my most sparkling eye, with my most animated gestures. And if she asks me whether Santa is real… well, I suppose that I’ll be honest with her. I’ll say that real can mean many things; I’ll say that sometimes it’s enough to believe in something with all your heart to make that thing real in many of the ways that count (to love that thing, to derive hope or comfort or inspiration from that thing). I’ll say that while there is no current evidence of a toy workshop at the precise location of the North Pole, that doesn’t mean that it isn’t possible that there is a Santa, somewhere, or that even if there isn’t a living human man named Santa Claus, that doesn’t mean that the spirit of Santa isn’t in its own way real.

I will say that, in any case, whatever one believes about Santa Claus, it is very important to believe, sometimes, in impossible things. I will say, with the Queen of Hearts, that I myself have been known to believe in as many as six impossible things, all before breakfast.

I will say that one of those things has always been and will always be Santa.

I will say that one of those things has always been and will always be Santa.

All of which is to say that I will encourage her to reach her own conclusions, and that I will encourage her to be broad-minded in pursuing those conclusions, in pursuing understanding of seemingly impossible things. I will give her the opportunity to believe in impossible things, to embrace the stories of impossible things and to let them live in her imagination. I will let her have her Santa, whatever that means, if she wants him, for as long as she wants him, however she wants him. And I will be right there with her, writing the letters and putting out the cookies and worrying about the reindeer and – one day, when that day comes – talking about the lovely truths hidden within these stories and these actions and the spirit of these impossible things.

Happy holidays. May you enjoy your own impossible things.

(Parts of this post have been repurposed from a years-ago piece on Santa and noble lies. Substantially rewritten, but some key plot points – Plato, noble lies – have been incorporated. Because this is all part of one much longer story.)