(I posted a version of this piece a zillion 8 years ago. Republishing it now, because I feel like it.)

Today, we’re going to talk about books.

Not about books that you should read (I can cover that topic another time), nor about books that I currently read. It’s about one of my very first books. One of the first that I can remember holding in my own hands. It was not Alice in Wonderland or Peter Pan or Ivanhoe or Alice in Wonderland or Little Women or any of the tales told by the Brothers Grimm or Hans Christian Anderson (all of which were read aloud to me many times before I ever got my hands on them.)

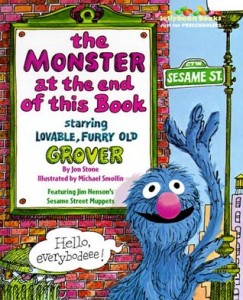

It was this:

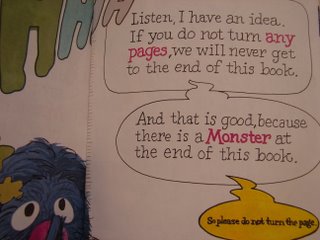

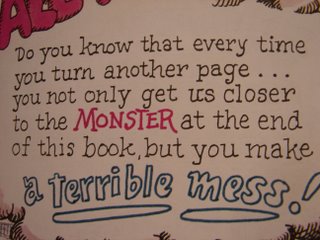

It was a Little Golden Book, starring Grover. The plot (such as it is) hinges upon the promise made in the title: that there is a monster at the end of the book. Every time you turn a page – against Grover’s exhortations that you not, for the love of all that is blue and holy, turn the page – you get closer to that monster.

Every time that I opened this book, I thrilled at the suspense. When either of my parents read it with me, I would squeal and grab their hands: Careful! Turn the pages slowly! Slowly!

Every page was turned carefully, slowly, one corner at time, so that I could peek around the printed corner. I knew well what was coming, but I still squirmed with anticipation and the teeniest, tiniest flicker of fear…

… and a delicious sense of naughtiness. Grover – lovable old Grover – says please don’t turn the page. Mom or Dad would say, are you sure you want to turn the page? Grover says don’t turn the page. But still, always, I turned the page.

And I would, always, shriek with delight when I reached the end, where, as promised, the monster was revealed.

That the monster was Grover was never a surprise, not after the first reading. What thrilled and delighted me, I think, was the reminder – the ever unexpected reminder – of Grover’s monsterness. I knew that Grover was a monster, of course. But I never reflected upon his monsterness. I never – that is, when I was not turning the pages of this particular book – gave any thought to the fact that Grover was a monster, or to the fact that his monsterness put him in the same category as Boogeymen and werewolves and all other manner of frightening creatures that lived under my bed or in my closet. Grover was familiar and safe and comforting (in a way that the Cookie Monster, for example, was not. I always suspected that the Cookie Monster could turn on a kid at any time, revert to his monster-ish, Mr-Muppet-Hyde dark side while in the grip of a bad cookie trip.) Grover was not monster in the sense of being Other: he was a sweet old furry blue uncle, very possibly with bad breath, but certainly generous with the hugs.

The book gripped me with the revelatory reminder that he was, indeed, a monster. It also, of course, gripped me with its narrative suspense. I think that this book was a wonderful introduction, for a very young reader, to the thrill of the page, to the incomparable magic carpet ride – destination unknown or anticipated or delightfully feared – that is a good story. And it demonstrated amply that a good story can boil down to just a few simple, well-directed lines.

It was all of these things. But it was mostly the thrill of being reminded that Grover’s a monster I’m supposed to be afraid of monsters but I’m not afraid of Grover the monster that kept me pestering my parents to sit down and read this book with me.

Roland Barthes argued that there is pleasure in narrative suspense – the “gradual unveiling” of a story – but that this pleasure is not the true pleasure of the text. The text of pleasure, he says, submits to and offers comfortable reading; the text of bliss, on the other hand, discomfits. It unsettles the reader’s assumptions, “brings to a crisis his relation with language.”

The thrill of There’s a Monster at the End of this Book was, for me, exactly this. It exploded my childish understanding of ‘monster.’ And, more to the point, it broke the comfort of my readerly relationship with Grover; it unsettled my assumption that Grover was just like me (because do we not assume that those whom we love are always and ever just like us?) and forced me to confront dear Grover as the alien being that he is. If I love Grover, I love monsters. The book was thrilling because it was sort of dangerous. It provoked a little bit of fear and then asked me to reconsider that fear. It asked me questions. It made me ask questions. Why was I – am I – afraid of monsters? Who else is a monster? WHAT is a monster?

That book (and others like it) turned me on to the thrill of having my assumptions challenged. It fueled my love of questions. And, it made me love books. It made me love the adventure of opening books to see what surprises they held.

It was good stuff. Still is. I nearly wept when I found There’s a Monster at the End of This Book at a second-hand store the other day, and when I sat down with Emilia to flip through the pages (and found myself doing a strange, Yoda-ish impression of Grover that completely failed to impress) it provoked the same old thrill. Well look at that! This is the end of the book and the only one here is ME! Grover!

Well, Grover, and some good old-fashioned structuralist/post-structuralist literary analysis. Here be monsters.