Every visit to the doctor, now, brings bad news. In the early days, there were reassurances and messages of hope – some boys make it out of their teens, there are ways to slow the deterioration of his muscles, he might stay mobile for a long time, he might still get to enjoy some of his boyhood in the ways that other boys take for granted – but now, there are only somber descriptions of what will happen next, of what needs to be done to make things easier, of what use can be made of his diminishing time.

Every visit to the doctor, now, brings bad news. In the early days, there were reassurances and messages of hope – some boys make it out of their teens, there are ways to slow the deterioration of his muscles, he might stay mobile for a long time, he might still get to enjoy some of his boyhood in the ways that other boys take for granted – but now, there are only somber descriptions of what will happen next, of what needs to be done to make things easier, of what use can be made of his diminishing time.

They want to put rods in his spine, she tells me. So that he can stay upright for a bit longer.

Rods in his spine. He won’t be able to bend, I think, before remembering, he cannot bend now. Not in the real, active sense of bending, anyway: he slumps, he droops, he slides forward in his chair, unable to hold his own weight even while sitting, a Pinocchio without strings. His spine is collapsing under the weight of his body, his muscles having deteriorated beyond the point where they can provide any support. He’s like a doll now, a puppet. But he has no strings by which he might be pulled up. He has no Blue Fairy to wave a wand and make such strings unnecessary. He has only surgeons, and rods.

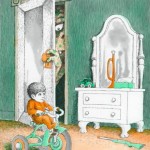

It is, of course, our greatest fear. It is the bogeyman in our closet, the monster under our bed. It is the shadow that lurks behind every tree in the wood, it is the crackle of every twig, it is the sudden silencing of birds, the darkening of the sky, the unexpected chill in the air, the thing that stops our breathing, that quickens the beat of our hearts. And we cannot tell ourselves that it isn’t there, that it is just the stuff of fairy tales and scary stories; we cannot shine the flashlight into the closet or under the bed or out toward the trees and reassure ourselves, because it is out there, it is, maybe just as a possibility, maybe just as the faintest possibility, but that possibility is what gives it air to breath and matter to take form.

It is, of course, our greatest fear. It is the bogeyman in our closet, the monster under our bed. It is the shadow that lurks behind every tree in the wood, it is the crackle of every twig, it is the sudden silencing of birds, the darkening of the sky, the unexpected chill in the air, the thing that stops our breathing, that quickens the beat of our hearts. And we cannot tell ourselves that it isn’t there, that it is just the stuff of fairy tales and scary stories; we cannot shine the flashlight into the closet or under the bed or out toward the trees and reassure ourselves, because it is out there, it is, maybe just as a possibility, maybe just as the faintest possibility, but that possibility is what gives it air to breath and matter to take form.