I think that I’m stuck in the denial stage of grief. It’s not that I deny the fact that my father is dead – his ashes sit in a box on my mantle, surrounded, at the moment, by a few Christmas ornaments and my kids’ picture with Santa and Emilia’s bardo-drawing – it’s that I can’t wrap my head around the fact – is it a fact? – that his death is the end, that his life is over, that I’ll never see or speak with him again. The absoluteness of it all, the finality: I’m having trouble accepting this. I can’t accept this. My heart aches from its stubborn refusal to accept this.

I wanted this year to start with laughter and smiles and cookies and fizzy soda. I didn’t want confetti and champagne and fireworks and streamers – I just wanted smiling. I just wanted this year to start happy.

I’m still trying to find the happy. Yes, my heart lifts when I hug my children and my lips curve when they giggle but the last week of last year and the first week of this year have been covered in a thick blanket of fever and snot and heartache and it’s been hard to find the laughter. And although Nyquil takes the edge off the fever and snot, there aren’t sufficient meds for heartache, Ativan and Xanax notwithstanding. Last week was much, much harder than I thought it would be – doing the final clean-up of my dad’s place in the week between Christmas and New Year’s was, in hindsight, less than ideal timing. Coping with the heart-punches of the holidays was difficult enough without throwing myself into the line of fire of the gut-kicks and soul-wedgies that came with seeing the last of his things carted away, his home wiped clean of his presence.

When I received the call telling me that my father had died, I cried. I cried loud, I cried hard, I fell to the ground and clutched at my aching chest and I wailed. And then, curled up on the floor, phone in hand, I tweeted.

I tweeted because it was instinct. I tweeted because it was the only thing that I could think of to do. I tweeted because I needed to get the words that were reverberating in my head and smashing against the walls of my mind out out out and into the world so that I could step back and see them/hear them/feel them and know that they weren’t just the narrative of some nightmare conjured up by that corner of my soul that holds and nurtures its darkest fears. I needed to face the words, and know that they were true. I needed to take control of the narration of the terrible story that was unfolding. I needed to speak. I needed to write.

So I tweeted.

My dad was a hoarder. When he died, they had to cut through the outside wall of his house to remove his remains. There simply wasn’t room for the coroner to get him through the packed hallway, the corridors lined with stuff. They cut a hole in the wall and pulled out the contents of the room. Including my dad.

Someone thought to board the wall with a piece of plywood, afterward.

The coroner said to me, if you don’t have to go there, you maybe shouldn’t. Someone else said, see if the insurance company will hire cleaners. Someone else said to me, if you go, you have to remember, this is not who he is.

I went. I was afraid, but I went.

My mom came with me. When we got there and went inside, she cried. I stood in his kitchen and looked at the boxes and the books and the electronics and the crocheted wall hangings and the computers – the dozens of computers – and the tools and the CD cases and I ran my fingers over a stack of disemboweled laptops and I thought, oh, Dad.

I might have actually spoken the words aloud. I can’t recall. Oh, Dad, I thought. You had nothing to be ashamed of.

I’m stuck.

I have a whole post, one that is already written, down to a word, in my head, one that is pounding against the binding of my brain and demanding to be released. It’s a post that I’ve had written for weeks, months, and that I’ve kept tucked away, unsure about whether or not to publish it. And then, in the past week, discussion began to swirl online about issues related to the thing that I want to talk about – that I want so badly to talk about – and I found myself trailing my fingers across my keyboard, straining against the urge to write and hit post, write and hit post, write and hit post. But I resisted – I am resisting, so far – and so I have been pecking at tweets and making cryptic remarks to nobody in particular because it is bothering me, it is really bothering me, and I want so badly to lay it bare upon the screen and shout, see? See? This is why! This is why! This why you need to look at this differently, this is why these discussions are wrong, this is why I have been sitting here, grimacing and fighting back tears.

Because this matters, to me.

I don’t believe in petitionary or intercessory prayer. I’ve written about my reasons for this at length, but it boils down to this: I don’t believe in, can’t believe in, a God who responds to such prayer. As I said some months ago, ‘why should God help us find a cure for cancer, and not for muscular dystrophy? Find one lost child, and not another? Help the Red Wings win while leaving children dying in sub-Saharan Africa? If God is a god who lets bad things happen, the only way that I can understand that is if the point of letting bad things happen is to compel us to cope with pain and heartbreak and evil ourselves, alone, to better understand those things. And that idea of a didactic God doesn’t square with a picture of God as a moody patriarch who dispenses favors to his children on the basis of who supplicates most fervently.’

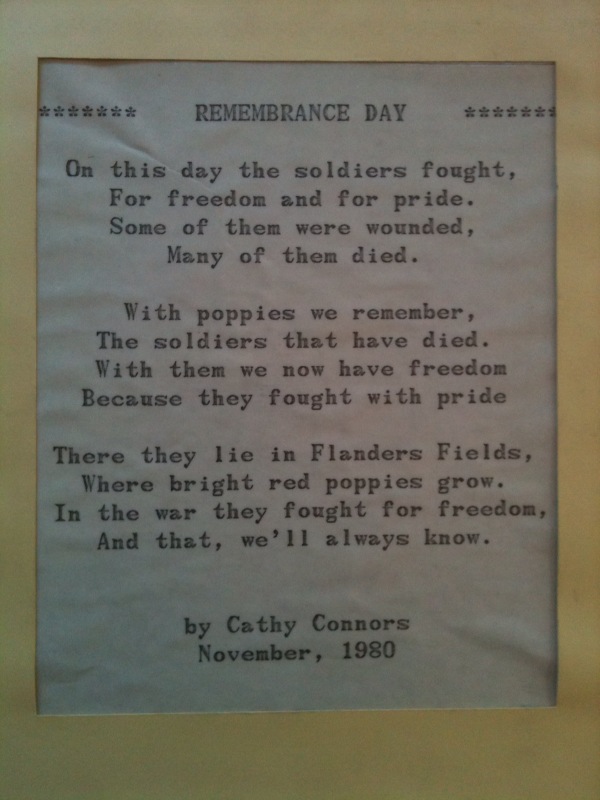

I wrote this poem for Remembrance Day (Canada’s Veteran’s Day) when I was in third grade. I was very proud of it: I was asked to read it at that year’s Remembrance Day assembly in my elementary school, and I was the youngest of the students up on stage. I can’t remember much about the reading, only that my heart was pounding and that when everyone bowed their heads for the moment of silence I peeked out from under my bangs and watched to see who in the gymnasium full of kids was picking their nose or poking their neighbor and from my vantage point on the stage felt giddy with the sort of puffed-up childish superiority that only small children on gymnasium stages and politicians can muster. Which is not the point of Remembrance Day, but still. It was a silly poem, I thought once I’d grown and moved on to the angst-ridden tumult of free verse, a silly poem full of all the earnestness and dryness and commitment to basic rhyme schemes that is characteristic of small children with literary ambitions.

A few weeks ago, I said this about Hollywood’s defense of Roman Polanski:

What message does it send to our sons when the rape of a young girl is dismissed as something that is not that bad? What message does it send to the would-be Donalds of the world? To the would-be Roman Polanskis? To all the boys and men (and, yes, perhaps, women) who would grab and grope and hurt and rape, and to all the boys and men who wouldn’t? That sometimes, it’s okay? And that even if you wouldn’t do it, you shouldn’t necessarily condemn someone who does grab or grope or rape… who? Your sister, your mother, your wife, your lover, your daughter, your child?

I could not have imagined, when I wrote those words, that one might also have added this suggestion: that it’s okay to stand by and watch as a young girl gets gang-raped.