Here’s a question that I’ve been thinking a lot about: what does it mean to say that you have purpose? Or that you have a purpose? Do you have to be able to define your purpose in order to have purpose? Or is it enough to be (or feel) purposeful – that is to say, motivated or driven by a sense of purpose, even if you can’t really define what the specific purpose is?

Is it enough to just want to contribute to making the world a better place? To simply having a net-positive impact upon the world? To leaving it at least just a little better than how it was when you arrived? Or do you have to be able to explain how and why you’re doing that?

All the experts will tell you that goals, if you’re to have any chance of meeting them, need to be defined. Spelled out. Written down. Charted and tracked. You need to state them and record them and connect them to key performance indicators. You need to assert your intention to the universe, or at least document it in your bullet journal. And purpose is just another kind of goal, so it follows that the same principles apply.

Maybe.

I’ve never actually clearly defined my purpose. I didn’t even start thinking in explicit terms of capital-p ‘Purpose’ until a couple of years ago, when I was grappling with the decision to leave Disney, and only then because some wise friends and counselors urged me to approach the decision in that way. But it’s always been there. It was there when I chose my academic paths; it was there when I chose different academic paths; it was there when I left academia altogether. It was there when I worked from home. It was there when I worked outside the home. It was there when I gathered up my family and left our country for new horizons. It’s been there ever since. I just didn’t always call it that.

There have been consistent threads of purpose. Storytelling. Community. Women and the family. The intersection of these. I once said to a friend, years ago, that the wild, circuitous path of my career made sense to me only when I looked at it through the lens of my heart and noticed this: that every choice I’d made, every sharp turn or gentle deviation along the path, could be distilled down to my passion for these (for lack of a better word) purposes. They, together, formed a sort of compass. As long as I followed it, I knew I’d stay well-directed.

This was before Disney – this was, indeed, on the cusp of the acquisition by Disney, in the period when Disney was still a secret that I couldn’t share, before I really knew just how wildly circuitous the road could get. The compass pointed to and through Disney, too. All I knew then was that it was the right choice to follow it.

And it really was.

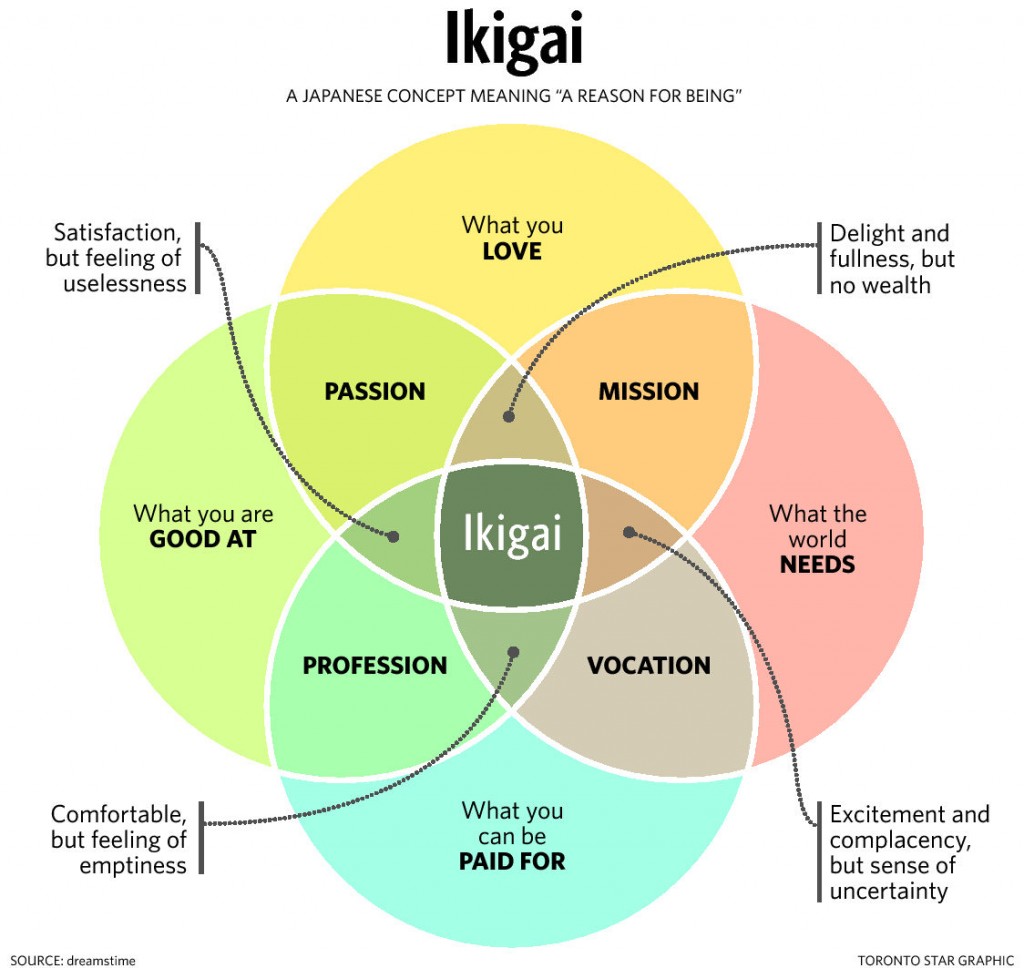

The compass has brought me to four of the five intersections of the Ikigai diagram. The fourth, the middle, I’ve gotten to only relatively recently. Even though I might have said, in the past, that I had hit that inner circle, I wouldn’t have been correct, or correct enough to for it to really count. Because here’s the thing: while it’s pretty straightforward (straightforward-ish) to correctly determine what you’re good at and what you can get paid for, it’s a little tougher to pin down what you love (what you really love) and what the world needs (what the world really needs.)

For example: I used to think that I loved teaching. Truth was, I only liked teaching, parts of it, sort of. Years after I taught my last class, a good friend and colleague challenged me to get brutally honest with myself about what I actually, truly loved doing, and why. He said, “don’t give yourself the PR answer, the answer you’d give in an interview, the pageant answer – the answer that sounds good and reflects well on you – give yourself the true answer, even if it’s embarrassing. That’s the only way you’ll figure out what’s going to make you truly happy.” When I applied that in hindsight to teaching, I realized that I didn’t love the patient nurturing of young minds. I liked speaking. I liked working out ideas and then sharing them publicly. I liked being an authority. I liked the sound of my own voice. (I told you: not the pageant answer.)

Another example: when I was at Disney, I thought that what the world needed was me to get the company to do better by moms, and later, by girls. But that was a position of convenience: I was in Disney, and I had influence, and I identified a need that happened to correspond with my skills, my interests, and my position. Was it a true need? Not really. Does the world need Disney to sell Princesses with more girl-positive messaging? It does not. It’s a good thing, sure – much better to sell empowerment than weakness – but it’s not a need. I could – and did – make the case for its necessity (that’s another conversation for another time), but to the extent that I did that successfully, it only ever pointed to a very thin layer, a ‘nice to have’ rather than a ‘must have.’ Or at least, I could only ever believe that it was at most a ‘nice to have’ rather than a true need.

I wanted to play in the realm of true need and true love, of mission and passion. That’s not to say that I was never going to be happy until I did – I’ve been very happy with profession and vocation – and it’s not to say that others couldn’t find mission and passion in the things that I did not (there are absolutely true believers within Disney who believe with their whole hearts that the Princess franchise needs to be a force for good, and I love those people.) But I could only find my own Ikigai by finding what I truly, deeply love, and what I truly, deeply believe is a need. So I left to find it.

And I’m there, I think, or close. There’s been a lot of sacrifice and work – it’s a hard, hard path, I’m telling you (it’s SO HARD) – but it’s worth it. You know it when you’re there or close, because the work feels well worth it. Really well worth it. It’s not just you telling yourself that it’s worth it – you feel it, in your gut and in your heart.

So no, I don’t think you need to be able to define your purpose. You just need to be able to feel it. And in some ways that’s even harder.

But it’s worth it.